|

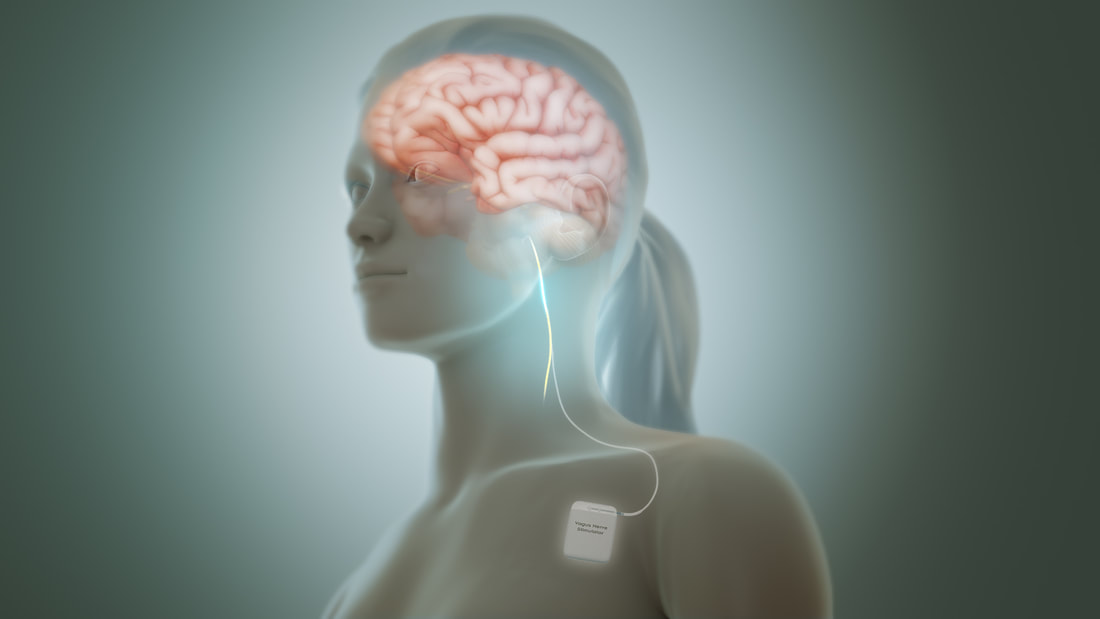

“ I’ve worked hard with this client, tried everything, but nothing seems to shift.” “ The client was clear what he wanted to change, and had the actions, but when he came back, nothing had happened” “I worked with this client a few years ago, and I thought we had done some good coaching. But she is back now, and clearly the changes I thought she had put in place in her life haven’t happened. The agenda feels very similar.” “This client was so driven in her goals to up the amount of exercise she gets, and to increase her productivity. I felt both in awe of her but I also felt a sense of unease as I wasn’t sure these were ways out of her exhaustion.” “My sense is that he is quite anxious, but he says he doesn’t feel that. It seems hard for him to think of creative ways of achieving what he wants.” “He seems so driven, he works long hours, without any play as far as I can tell and while he says he wants to do less, nothing has worked to change that.” Do these sound familiar in any way? Such examples illustrate clients operating through their survival self. When that happens, the survival parts that resist healthy change are uppermost. Such situations often encourage coaches to move into one of our survival parts too, for example, rescuing, trying hard, upping our expectation that we must be a ‘good coach’ to break through this stuckness, or deciding we are a ‘bad coach’ for getting into that situation in the first place. The survival self and parts are these defensive behaviour, thoughts, and feelings which are designed to keep us away from what lies deeply behind them, that is, the trauma feelings of fear, pain, helplessness, rage or abandonment. The trauma feelings come from early experience when we couldn’t get away from the environment we were in, and our neuro-physiological systems responded as if our life was in danger. When the environment in the ‘here and now’ is triggering old patterns of fear and lack of safety, most often out of conscious awareness but our body feels them, the survival self and parts are uppermost in an attempt to keep us safe. Stephen Porges, a neuro-physiology academic in the USA, has studied the function of the vagal nerve within the central nervous system over many years of research. Porges refers to his work as polyvagal theory, which you might have come across. He calls it the biology of safety and danger. Although Proges’s research was not connected with trauma, his findings make a major contribution to the understanding of survival adaptive behaviour. To over-simplify the science, the vagal nerve runs from our brain down through our gut and is a major highway for data to and from the brain about our physiological responses to the external environment. It enables the body to act as a polygraph continually picking up clues from the external environment about how safe or not it is. The vagal nerve also responds immediately to the facial expressions of others and how safe we feel in their presence. This social engagement process is anthropologically essential for us as mammals as we need others and are social beings. Our worst fear is of isolation and we become vulnerable to not feeling seen, wanted or needed. If our early environment was unsafe, for whatever reason including high anxiety in our close care givers, our social engagement system is already on ‘red alert’. This gets replayed in adult life. Alongside this can be deep feelings of shame, which can produce self-criticism and a sense of inadequacy which we need to hide. Anxious people, those who don’t feel safe, can be very productive, as a lot of energy comes from that anxiety and they work hard. However, creativity is inhibited and anxiety-fuelled living feels very unsafe, if we ever stop long enough to allow those feelings to arise. We need to feel calm, and thus safe, for creative work. Coaching for personal change needs creativity, a capacity to engage calmly with reality, and decide what we want for a healthy life. Because anxiety and a sense of lack of safety feels so familiar to those who are traumatised; it is experienced as ‘normal’. They may not report that they feel unsafe or anxious. However the signs of such anxiety will be observed in being over busy, exhausted, trying to balance a lot of things, wanting to survive, wanting to find a place of imagined safety ( e.g. in a new job, or safer job) or to find someone to look after them (however unsuitable for that task, trying to please a boss who is hard to please). Over stimulation of the vagal nerve also results in irritable bowel syndrome, digestive problems, exhaustion and other physical symptoms. Many who have issues with safety and anxiety are also sensitive to noise; as that is outside their control the lack of sense of safety is enhanced. The neuro-physiology of the body has to be convinced the environment is safe before it gives up its survival defences. We need to be in a safety state for creativity and the higher brain function which can assess the actual level of danger in the ‘here and now’. Porges says ‘safety is more than the removal of threat, it is can you feel safe enough to give up your control to another person?’. Or in coaching terms, can you feel safe enough to creatively think though, with your coach, what you need for your life right now? The survival parts are signs of this lack of safety in both the client and coach. We can feel anxious if the coaching isn’t progressing, we can worry about our reputation and about future work. Will we be banished? When faced with what we hypothesise are survival parts, what should we do? We need to check in with ourselves. Are we in a calm creative state or has our vagal response been stimulated? If we sense we are not, we need to do what we can to get into that place. This might include taking a deep breath in and exhaling very slowly, as slowly as possible. This helps diminish the activation of the vagal nerve. We can do this without the client noticing. Or we could invite clients to do it with us a few times, explaining it will help with the creative thinking that is need. We don’t need to go into the vagal nerve functioning with the client. We can invite clients to bring to mind times, or a time, in their life when they felt safe and at their most creative? When they have that memory, invite them to talk about the specifics of that time, what was happening, who was with them, where were they? We can ask them to hold onto that feeling from that memory and consider how they could get more of that in their life and work right now? With clients who know they are anxious and with whom you have had a conversation about their anxiety and feelings of safety, invite them to rate how anxious they feel most of the time out of 10, and how would they like to rate it out of 10? Then talk about what actions they might take to achieve that reduction. Listening to music, while doing nothing else, having more play, being out in nature, meditation are all ways that help reduce levels of anxiety and enable the healthy self to come to the fore. The aim is to support clients access a physiological state that allows for social engagement without triggering their adaptive survival parts. That is the resources within their healthy self. Julia Vaughan Smith #traumainformedcoaching #coaching and trauma Reading references:

Franz Ruppert : Trauma, Love and Fear. Green Balloon Publishing Julia Vaughan Smith: Coaching and Trauma: from surviving to thriving Open University Press Stephen Porges: The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology)

0 Comments

|

News blogArchives

May 2024

Access Octomono Masonry Settings

|