|

It is the issues and circumstance of the coaching which have been changed by the pandemic, but not the principles and process of coaching. They remain the same. We, as coaches, are of course affected, too, and may bring that into our coaching. We need to be sure that what we bring is valuable to the process and not our survival parts. These are just a few of the issues to reflect on: HabitsThe pandemic, and the lock-down, have broken many of our habits, our established ways of structuring and organising our engagement with the world. We are being required to establish new habits. At the same time, it gives us an opportunity to think which of our habits do we want to let go, following this phase and which new ones might we want to put in place? For example, with developing skill in using online platforms for meetings, could that continue for parts of our work? For coaches, it can widen our client base nationally and internationally. Many coaches already work in that way and have skills and learning they can pass on. For clients, it may lead to a rethink of how they want to organise their work. Some clients may welcome the requirement to be at home, even to stop work (for those furloughed), and enjoy the absence of the daily travel and the other work-related habits. This may bring about some enquiry about ‘what would I rather have from now on, if I could have it?’. There will be those who face a major change in their work habits. For example, if their business or the focus of their work is changed forever by the pandemic. I am thinking of small businesses, the retail and hospitality industry and the tourism industry. However, coaching has approaches for supporting clients in this situation. It may be more intensive than pre-pandemic but we can help the client hold their vulnerability and self-regulate so that they can think their way through their situation. Performance expectationsIt is unrealistic to think that most of us can achieve the same level of ‘performance’, that is work outcomes, at this time. There will be exceptions of course and some may find that the opportunities for entrepreneurialism are liberating and their outcome is enhanced. For others though, they are learning how to use online platforms effectively, how to stay connected in meaningful ways with work colleagues, how to juggle the boundaries and demands of being a home-worker. This learning takes time. Working online can take away our boundaries, between home and work, and who has access to us, and when. It helps to be aware of how these boundaries have been broken down by the pandemic and what ones need to be put in place as part of this new learning. Thought habitsIt is also an opportunity to notice and reflect on our thought habits; those thoughts that emerge in response to the situation and what is required of us. They could be thoughts about danger and lack of safety, or about our self-worth or our isolation. These are usually negative thoughts that leave us feeling worse than we would if we could think something differently. We all have thought habits, we hear them as our clients talk and we hear them in our own heads. We can capture these and write them down and identify what feelings they generate and what behaviour that leads to. We can change our thoughts without escaping into positive illusion. “What could I think instead, which would still be authentic?”. I am using the term authentic to refer to that sense that it connects with our inner experience. Isolation impacts on us all, for some more than other. Especially affected are likely to include those where isolation is a feature of their earliest experience for example, hospitalisation as a child or being passed through the fostering system, or with parents who were unable to connect with us. This experience in the ‘there and then’ and can be recreated in the ‘here and now’ if we tell ourselves how isolated we are. The question is ‘how am I isolating myself, now?’. We can become identified with those who isolated us and with the experience of being isolated, that we fail to take healthy action for ourselves in the present. Similarly, if we feel uncared for in the present, we may well be identifying with the past. The question is ‘how am I failing to care for myself now?’ or ‘how can I feel my own love and care for myself?’ Many of us will have to practise these kinds of enquiries as our identification is a survival strategy from ‘there and then’ and has become such a thought habit that we often don’t even notice it. Like all habits, we only notice them when they are taken away or when we set out to pay attention. The stories we repeat about our past are also thought habits, we use them to reinforce our feelings of not being wanted, loved or protected in a way that we feel is in our control. Those feelings are there, the pain of them remains in the trauma self, but ironically using our stories to keep us imprisoned in the ‘here and now’ blocks our ability to connect with and process the pain. This became clear to me, personally, last week when I was reflecting on some writing I was doing on mothers and daughters and thinking about memoir writing. Was I using the story to ‘justify’ my thought habits and avoid looking into myself for my own capacity for self-love? We can support our clients to see their thought habits and decide how useful or avoidant they are to them right now. Fear and anxietyIt is understandable that there are heightened feelings of fear and anxiety at this time. Those whose core position is not to feel safe, due to their history, are likely to feel these acutely. Often, behind these feelings will be thought habits fuelling them too, that is bringing the past into the present which is not as dangerous as the response implies. We can explore these in ourselves and with our clients. We can help our clients develop processes that support their self-regulation. If we are in a state of fear or anxiety, we cannot find a place of safety, we become frozen. If we are sufficiently free of these emotions with our clients, we can act as a co-regulator with them. We can listen, be with their vulnerability, and support them in accessing other parts of themselves which aren’t overwhelmed by these feelings. Remember, working with parts is a very valuable process (see Sept 2019 blog). GuiltI feel in a bit of a bubble here in East Devon where the virus numbers are low, and I have a sunny garden and the sea is a 5 minute walk down the lane. I was part of an online group discussion on Saturday, and heard again (having heard it several times from friends) ‘I feel guilty that I am quite enjoying the lock-down and can get out, when so many can’t’. I have also had conversations with friends about ‘I feel I should be making a contribution by doing something’. The important thing to hold onto is that it isn’t either/or. We can feel privileged in our situation AND feel compassion for those that are in vastly different situations. We can decide if we want to take any action, and if so, what; and it is okay if we do or we don’t. The ‘shoulds’ are the clue to these being the equivalent of ‘parental injunctions’. We can also use this pandemic to become more aware, if we chose to, of the divisions and differences in the society we have helped create. Guilt is only useful if it triggers some thing we need to learn about how our action has transgressed our value system; for example, if we have stolen something or spoken harshly. Feel it, note it, move on. Often though it is a seeping ‘sore’. A friend sent me this in an email exchange about guilt: ‘and guilt, like the autumn leaves, has served whatever purpose it ever had and now withers, flutters and becomes useful as compost. ‘ We need to be sure that what ever action we take comes from our healthy self and that it isn’t a ‘reaction’ from our survival self needs for validation or rescuing. In terms of what to say to those who talk of their different situations, if we are truly listening from our health self resources, we will be connecting with the client and the words will come. If we are in our survival self we won’t have that connection and we may well say something that doesn’t land well. If we can stay in our healthy self-regulated state a lot of the time, we can be with our clients in whatever situation they come to us in. We don’t need new tools and techniques. We just need to listen fully, be present and use our coaching expertise effectively. Julia Vaughan Smith Author: ‘Coaching and Trauma: From surviving to thriving’ www.juliavaughansmith.co.uk #coachingandtrauma #traumainformedcoaching The image is a photograph of a much loved painting by Howard Fazakeley, who kindly gave me permission to use it in our publicity.

0 Comments

Since the social isolation started three weeks ago, I have observed my own survival parts activating as my autonomy and freedom is limited and I am physically isolated from those I love and care about. For many of us this stimulates our early trauma emotions which switches quickly to survival behaviour. I noticed this morning a sadness from grief: I could feel that sadness and loss, but I was also aware of a potential shift into survival self-pity. Could I just allow the sadness to come and then go?

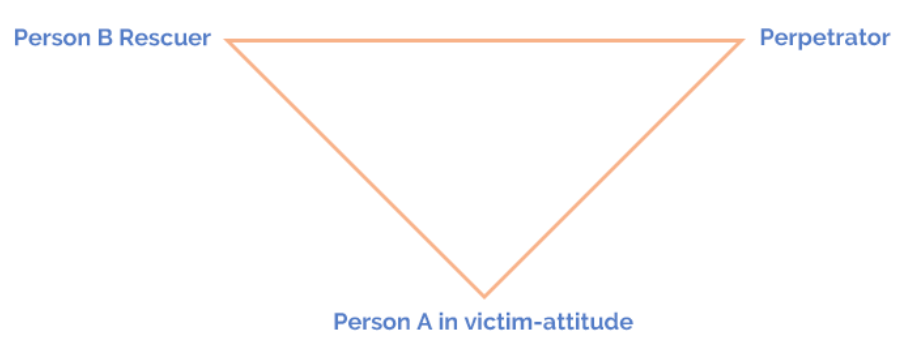

We will all have seen our own survival responses and those in the communities we are part of. Our rush to judgement, maybe, at those not ‘abiding by the rules’; being bad tempered and easily offended; being in ‘survival manager’, a form of control; denial; numbness, drinking more; or falling into a ‘victim attitude’. Some people might have become addicted to social media or the news in an attempt to manage their fear, when often it does the opposite. At the same time, there have been many examples of generosity of spirit, kindness and compassion and creative endeavour which come from a healthier place. For some, the enforced situation is bringing positive experiences of connection and slowing down. Families and work colleagues have found different ways to stay connected and look out for each other. Some people might experience the trauma response of freeze and fragment in the ‘here and now’, particularly those who are critically ill. For most of us though, it is likely to bring re-traumatisation. The level of this will vary, depending on our current circumstance and our history. Our response is due to the level of actual risk to life (as perceived by our neuro-physiology) in the present plus that which is triggered from the ‘there and then’. I have been thinking about the healthy self, how important it is that we are able to invoke that part within ourselves and how challenging that can be in stress-inducing circumstances. I was asked at one of the Masterclasses to say more about the healthy self, and I realised that I had been talking about it as an intellectual idea rather than an embodied sense of, and connection with, ourselves. When we are in our ‘healthy self’ we have reduced our stress and anxiety levels, and through so doing we can find a place of safety within. Many of us have anxiety levels set at a high ‘normal’ rather than one which is congruent with feeling safe. The healthy self is a place of grounded connection with our inner experience, where the data from our body can be accessed and processed by our frontal lobes, and where the responses of the ‘reptilian brain’ of fight, flight or freeze are not needed. Of course, these responses are vital when we are in actual, immediate danger. However, when they are constantly being reactivated by retraumatisation rather than the ‘here and now’ they drive survival behaviour, which is not about living but surviving. They are also damaging to our immune system, so at this particular time are very unhelpful to our protection. This connection with the healthy self , via self-regulation, needs regular practise using techniques or processes which bring us into that state of calm connection with ourself. We are so used to flipping from trauma pain into survival responses that we need to practise being able to connect with a different part of ourselves that can bear and process the pain. When we are in a calm, grounded state we can sue the reflective capacity of the human brain to enquire into our felt experience. Having ‘a practice’ to develop this ability, means using deep breathing techniques, mindfulness, meditation, listening to music, reflective journaling and similar approaches to calming the anxiety and connecting with an internal sense of safety. Any approach we use needs to result in a connection with our body and our internal experience, and to shut down the ongoing chatter in our brain. In our healthy self we can be aware of what we are feeling, for example my sadness this morning, and allow it to exist. We don’t need to push it away or block it out with activity or distraction. We can welcome it and allow it to go when we have acknowledged it. We can feel into our body, and explore which parts feel strong and which parts feel more vulnerable? We can note those without taking action. Some might then make an image that captures this experience or comes to us as we breathe deeply. We can reflectively explore that image to arrive at some understanding of what is going on for us. Some approaches may be more difficult at this time, for example, contemplative walking or spending a lot of time in nature. However, rather than become angry or turn to a ‘victim-attitude’, we can find other approaches or ways to get a similar experience. We are resourceful, we can find ways and practise them regularly during during each day to practise self-regulation and connection with the healthy self. We don’t need to spend a lot of time but enough to build up our ability to reconnect with ourselves in this strange and demanding time. As coaches, if we can do this, we can also be more available to our clients and help them find that place of inner safety too. Julia Vaughan Smith The Drama Triangle, familiar to many, developed by Stephen Karpman, is Transactional-Analysis model. It describes what can happen in an interaction between two people. More of that a bit later after considering a few questions:-

How about your clients?

These are all survival parts in response to the developmental trauma that shapes us during our very early life and relationships. The rescuer is seeking love, acceptance, acknowledgement or inclusion; however, the strategy fails as it creates a survival relationship. Those who take up a victim-attitude are demonstrating a survival response from having been actual victims in the past when they had nowhere to turn and were powerless. An actual victim feels the terror, rage and humiliation of being treated in that way. A victim-attitude is an avoidance of taking responsibility for oneself as an adult, when we have different resources available, and where there is no actual danger to life. The feeling associated with victim attitude is a helplessness, loss of contact with a sense of self-agency but without the trauma feelings of being attacked. It has more of a whining tone. It is an uncomfortable part to be caught in, and it is important to understand the its roots. The snapper, the part who turns on others, is a perpetrator part; also an element of trauma survival dynamics. We attack from irritation, from competitiveness, from seeing the other as an object not as a person. How we might have been treated as children some of the time. In trauma survival, the victim-attitude and perpetrator parts are on either side of a pendulum, and we can swing from one to the other. One minute we feel helpless and look for a rescuer (of which there are often many to choose from) entangling them in our psyche dynamics, the next we can be berating that rescuer for being unhelpful, uncaring, and assuming a place of grandiosity in relation to them. Underlying this behaviour are feelings of fear, heightened anxiety, and vulnerability. Similarly, the rescuer can switch into the victim-attitude or to the perpetrator, attacking the victim they have decided to help, or talking badly about them to others. At no time do many of those involved see what their part of the entanglement is. An entanglement is when survival strategies come together in relationship, and do a dance from which there is no escape, in a misguided attempt to meet unfulfilled hopes and needs from the past. Understanding Professor Franz Ruppert’s, Split in the Psyche Model (see other blogs and my book Coaching and Trauma) helps place these survival parts within the survival self, stimulated through unconscious feelings from the ‘there and then’ being enacted in the ‘here and now’ due to subtle triggers in the environment. Now, back to the Drama Triangle. Many coaches will have introduced this to their clients with great effect as it brings these dynamics to the fore where they can be talked about and explored, as can the client’s part in them. Karpman didn’t develop the Drama Triangle to illuminate trauma dynamics, and to read fully what is behind the model and how it is used in Transactional Analysis see his website https://karpmandramatriangle.com/ However, we can adapt it to being trauma-informed. The ‘game’, using TA language, starts with Person A in victim attitude. They seek a rescuer and find Person B who is willing to ‘play’. Here the entanglement starts. Person A, expresses how over-worked they are, or how bad their life/work is, and Person B steps in to help or to do something they hope with rescue person A from those feelings and situation. But in so doing, they don’t realise the entanglement dynamic is not resolvable in that way, only keeps it going. Person A may feel a bit superior or ‘good’ about helping, they may also hope that it will get them some ‘love’ or recognition. Because it is a ‘game’ or a survival dynamic, at some point the process shifts. Usually Person A, in victim attitude, switches to be the perpetrator, accusing Person B of being unhelpful, bossy or generally making things worse. Thereby, Person A has shifted from being in Victim Attitude to being a Perpetrator, and Person B shifts into being an actual victim of person A’s attack. If they get stuck in victim attitude they might then go and see if they can find a rescuer and so on. Or Person B, in rescuer, might get fed up with the stuckness of Person A, and switch to perpetrator themselves, making Person A an actual victim of their attack and reinforcing old trauma memory pathways. Alternatively, Person A in victim-attitude may unconsciously look for Perpetrator to save them, which will not work out well for them. To protect themselves they may switch to rescuer in the illusion that they can ‘help’ the perpetrator be a nicer person. The ‘way out’ in TA terms is for one of the pair to step into the adult ego state, (as in Parent, Adult, Child ego states) and to observe the dynamics, to take responsibility for their part in it, and move away from rescuing or being in victim attitude. In trauma-informed coaching the way out is similar, to see the entanglement for what it is a misplaced desire for love, attention, retribution, to take responsibility for their own part and to use the resources in their healthy self to consider what is a better way to relate to this other person. How can they do that without inviting the other into, or stepping into, and entanglement? Using both Ruppert’s model and the Drama Triangle with clients (or ourselves) can be useful if we understand both fully and are skilled at introducing them into the coaching. Jules Vaughan Smith See my book ‘Coaching and Trauma: from surviving to thriving” published by Open University Press

Reading Franz Ruppert Trauma, fear and love Green Balloon Books |

News blogArchives

May 2024

Access Octomono Masonry Settings

|