Refreshing Leadership podcastS2.28: Thriving Teams: A Trauma-Informed Approach to Resilient Leadership with Julia Vaughan-Smith, Master Executive Coach & Supervisor

0 Comments

ForewordI prepared this for the Annual Transformative Coaching Summit. I was unable to do the session due to illness. Please do email me with anything that comes to your mind as you read and think about this: [email protected]. Julia Vaughan Smith. Here are just some of my reflections on this aspect of our practice. I start by reflecting on Presence and then move to explore my thoughts about ‘Fake’ Presence and Absencing. Trying to describe Presence in cognitive terms rather misses the point as it is all about Being - an internal state and experience. Having said that, I will do my best to articulate what I think it is. Being Present Presence and being present are key aspects within coaching and therapy. Our capacity to attune and connect to the client enables us to be with what is, to listen intently and feel a resonance with the other. It is also what helps create a sense of safety, essential when working with personal change and growth. The term Presence sometimes implies that the practice is straightforward , however, having practised as an Executive Coach, Psychotherapist and Supervisor for many years I can tell you it is not. It is something we need to learn how to do and have to work through those elements within us that stop us or take us into fake presence, absencing and distancing. ‘Fake presence’ is a term I am using to refer to our capacity to appear to be present on the outside, while not being present on the inside. I am assuming that many of us have experienced this, I certainly have. This is part of our protective armour against intimacy, having been vulnerable and hurt in the past, as children and maybe later in life. It is part of our internalised trauma response and a form of absencing ourselves from connection. Absence is the opposite of Presence. It is a way of desensitising ourselves. ‘Fake presence’ and absencing are not consciously created but a response to the situation; we can become aware that this is what we are doing or remain unaware. Our personal growth lies in recognising the difference between Presence and ‘fake presence’ and absencing. Working with our own trauma dynamics allows us to be as fully present as we can be more of the time. Definitions: Let’s start first with some definitions of the word Presence:

It is also the name of an album by Led Zeppelin for any of you old enough to remember that highly successful group from the 1970s! How I am using it in coaching and therapy is related to the first two of these but is more than just being present in the room with another; it is about being able to be in the present moment and feel the presence of the other through emotional attunement. That is, through Presence, we are able to resonate with the energy of the other. It means we feel the other within ourselves while remaining aware of ourselves in the moment. As Thomas Hubl1 says ‘we can feel us feeling the other feeling us’. It is subtly different to empathy which is a cognitive or emotional state, where we can connect with the situation of another. ‘Presence is a heightened awareness of our momentary bodily sensations, feelings and thoughts, which can expand out into a presence for others, attuned to their feelings and thoughts” Connie Zweig2 Presence is about no past, no future, just now, this moment. Without the capacity to be fully present, we can’t have emotional attunement; without emotional attunement we don’t have safety, and without safety we can’t have transformative coaching. If we are present, that is, grounded in the here and now, without thoughts from the past or about the future, but just with what is – while also being able to observe ourselves – we have the capacity for deep listening, witnessing, a sense of inner spaceousness and connectivity with the other. We can let go of ‘knowing’ and certainty, bringing ourselves fully into the encounter and opening up to the other. Attunement to the other, requires that we can attune to ourselves and our inner experience within our body, emotions and mind. Meditation can teach this. There is a link with the social engagement phase of Dr Stephen Porges’ polyvagal theory3, where we are calm, self-regulated (that is heartbeat and breathing slow and normal), curious, compassionate and open hearted to the other. Our facial muscles are relaxed and our eyes soft. We convey safety to the other. The term Presence came into use in organisational consulting fields in 2009 with the work of Dr Otto Scharmer and Theory U4. Theory U is concerned with how we come to collective new ideas and solutions within systems. It is a process used within groups wishing to bring about systems change. He refers to Presencing a process of letting go of our ego, old patterns and certainties to connect with a deeper source of knowing. For this he states we need an Open Mind, Open Heart and Open Will. From this process, the future can emerge, not from an idea but from within. There are similarities with how I am using Presence. We do need to let go of our ego needs and the need ‘to know’ or to have certainty, and we do need an open mind and an open heart. Roshi Joan Halifax5 talks of the need for leadership and compassion, to have a strong back, a soft front and an open heart. Pause: take stock within yourself Check in with yourself right now, how present in the moment do you feel? Is your mind running about the past or the future? Is your mind critiquing as I go along? Check in with your body, is it grounded? What about your breathing, just take a moment to notice it. Without judgement, just notice. If you feel nothing in your body, that is okay. Honour and respect whatever comes up as you sit with yourself. Why is it important? We know from childhood studies that the capacity of key care-givers, particularly the mother to attune to her child is key to their emotional development and to positive learning about themselves. Our first mirror is our mother’s eyes, as stated by Dr Donald Winnicott6. If this, along with that of other care-givers is loving and attuned, we learn that it is safe to be in emotional connection with another, and from that we learn how to be in emotional contact with ourselves. In coaching, counselling and therapy, we want to create a safe space, where the client can feel met, seen and can enter into fully as themselves. While this is difficult for some or many clients due to their trauma experience or neuro-diversity, it is our role to offer them our Presence. Such a space can offer clients the chance to bring themselves into a calm state, from which they can better observe themselves, their behaviour and thinking patterns, do the best thinking they can and connect with their emotional experience. This all supports personal growth and learning. We can only help clients to achieve their intentions if we can open ourselves to their presence, connect with them emotionally/phenomonologically as well as cognitively. That means being able to feel them within us, without merging with them or identifying with them or taking their emotions away with us. To understand being present we need to understand fake presence, absencing and distancing ‘Fake presence’ is when we can appear to be physically present, maybe even our body is relaxed and breathing calm but we are not open to the other, our mind is in charge. Or we may feel numb in our body and emotions, within awareness or not. To the other person, we may look as if we are present and available to them, and part of us might be, but other parts are not, they are closed off from the other- they are avoiding that connection. We distance ourselves, leaving a mask in place but stepping back so that we do not feel the other; clients will of course sense this but may not be able to describe what feels lacking. Absencing ourselves is another term for this withdrawal; it is the opposite of attunement. We can absent ourselves without using ‘fake presence’, in that situation it is clear, from the quality of our attention and physicality that we are not connected with the other. As children some of us developed the capacity to look as if we were listening and attending in class but weren’t. Obviously, any exam results challenged that, but in the moment we could fake it. Some people have developed that capacity to ‘send out’ a persona who engages with the outer world while the feeling person is kept safely hidden from the other. You may have experienced this is some clients, that they appear engaged and on board with the coaching but you feel you are not really connecting with them, that there is something missing. The reasons for faking presence and absencing are similar and all are due to the ‘there and then’ of our past experience operating in the ‘here and now’ of the relationship; or when we are very preoccupied with something outside the present encounter. Many of us find it hard to let go of thoughts about the future, possibly the outcomes of coaching and how we will be viewed, and perhaps memories of the past. We may cling on to knowing and certainty, feeling vulnerable without that. Parts within us may be agitated with the coaching encounter or in relation to something outside of it. Aspects of our psyche may not like the other, or warm to them or feel unsafe with them, and fearing repercussions we fake our Presence or absent ourselves. We may seek a connection to meet our own unmet needs for love or belonging from the past and become entangled. We may identify with the other believing that this is connecting with them but instead we have let go of our separateness and see us as ‘one’ with the client. From this position we can wrongly believe that we know what the client needs to do or how they should live. This is an entanglement. Sometimes ‘faking presence’ and absencing can be a good protector and we need to honour our capacity to use it, it kept us safe as children and in some relationships since. In coaching it is helpful to know when we are doing that and why, so that we can open up the space within for greater Presence. Faking presence and absencing can be out of our awareness, and usually is until we engage in personal reflection afterwards or as we catch ourselves being out of connection in a session or interaction. Our clients can ‘fake presence’ and absent and distant with us too, and some will be if they don’t feel safe or if they have had poor experiences with trust and intimacy. Not everyone can have an attuned felt experience, those who are neurodiverse and those who carry internalised trauma may find it challenging. As a trauma response, we can close down the connection between body, emotions and mind, and leave only the mind relating. This is a protective mechanism from a time when it was intelligent to do that. Why do we become avoidant or fake it? And what happens when we do? Faking, avoidance/distancing/absencing and merger are all protective/defensive responses to an intimate emotional contact with another. The roots to this probably lie in childhood and may have been reinforced by certain relationships in adulthood. Trust in the other, feeling safe with the other is very difficult so we use these responses to protect ourselves. When we developed these protectors, they were our childhood heroes, they enabled us to survive relationships that we experienced as unsafe, and for that they need to be honoured and respected. Dissociation is a more extreme form of distancing and is a symptom of being in the ‘freeze and fragment’ phase of a trauma dynamic. Here, the person is out of connection with themselves and with the other person, they have shut down and psychically withdrawn. It is a coping mechanism within some who are traumatised or under considerable stress, activating earlier trauma. Trying to ‘get rid of’ or engaging with self-criticism about these strategies is unhelpful and makes things worse. We need to engage with them, understand them, appreciate what they are trying to do and reflect on why we needed them. If we meet them in clients, it is important to do the same. Respect that they are there and that, right now, the client doesn’t feel safe enough to be open-minded and open-hearted with us. They feel the need to protect themselves. As long as we can stay present and fully open to the client, they may gradually feel safer. They may not. These survival protective strategies are the ‘there and then’ entering the ‘here and now’; they are from the past and are deeply established habits. If it is relevant to the client’s coaching intentions, we may choose to share our experience with a client whom we experience as distancing, without judgement, and share that we notice it seems difficult for the client to connect with us and wonder about that with them. We may not, it depends how we contract, and work, with clients. How do we stay present when the other is in avoidance/not connecting? A real challenge is how to stay in Presence when the other isn’t. It is much easier when the other can meet us from that place, but many can’t. Younger parts of our psyche can be activated through the lack of connection from the other. It may activate earlier childhood experiences and we may switch into protective behaviour. This might involve talking too much, directing the session too much, telling ourselves we are failing as a coach, or just letting the client talk without connection. Our mind gets active and our hearts close up. If you notice this happening, pay attention to your breathing, trying to calm yourself, and bring yourself back to a grounded position; become attuned to yourself. Focus on the client and your felt experience of them, become curious rather than judgemental, become connected rather than distanced, open up to a connection. Never diagnose the other, as that is part of distancing As with all discussions about relational behaviour it is important to recognise that some behaviour that is associated with a trauma response can alternatively be an element of neurodiversity. It is important that we never label a client as traumatised or make a diagnosis, we are not qualified to do that, and if we do. we are taking up an expert role where ‘knowing’ has become important. We have also turned the client into an object. In Presence, we meet the other as they are. What have you learnt about how to develop your ability to be fully present? How can you tell you are Present? Some of my reflections are: I know when I am Present when:

How I have learnt to develop my ability to be fully Present:

Summing up. I feel I have only scratched the surface. I hope, though, that it might stimulate some reflections and observations which are valuable for you and your clients. References 1 Thomas Hubl https://thomashuebl.com/ 2 Connie Zweig. ‘The Inner Work of Age’. Park Street Press. 2021 https://conniezweig.com/ 3 https://www.stephenporges.com/ 4 https://ottoscharmer.com/ 5 Roshin Joan Halifax.’Standing at the Edge’. Flatiron Books. 2018 https://www.joanhalifax.org/ 6 Dr Donald Winnicott, British Paediatrician and Psychoanalyst 1889 – 1971 Photo credit: Photo by Izzie Renee on Unsplash

I have been thinking a lot about this over the last year, stimulated by a programme I did led by Thomas Hübl1 and the Pocket Project2 on Trauma Informed Leadership and supported by working with other coaches in a small reflective enquiry group. A ‘White Paper’ and blogs by Meus.co.uk3 also fed into my exploration of what ‘trauma informed leadership’ is and what it has to do with coaching.

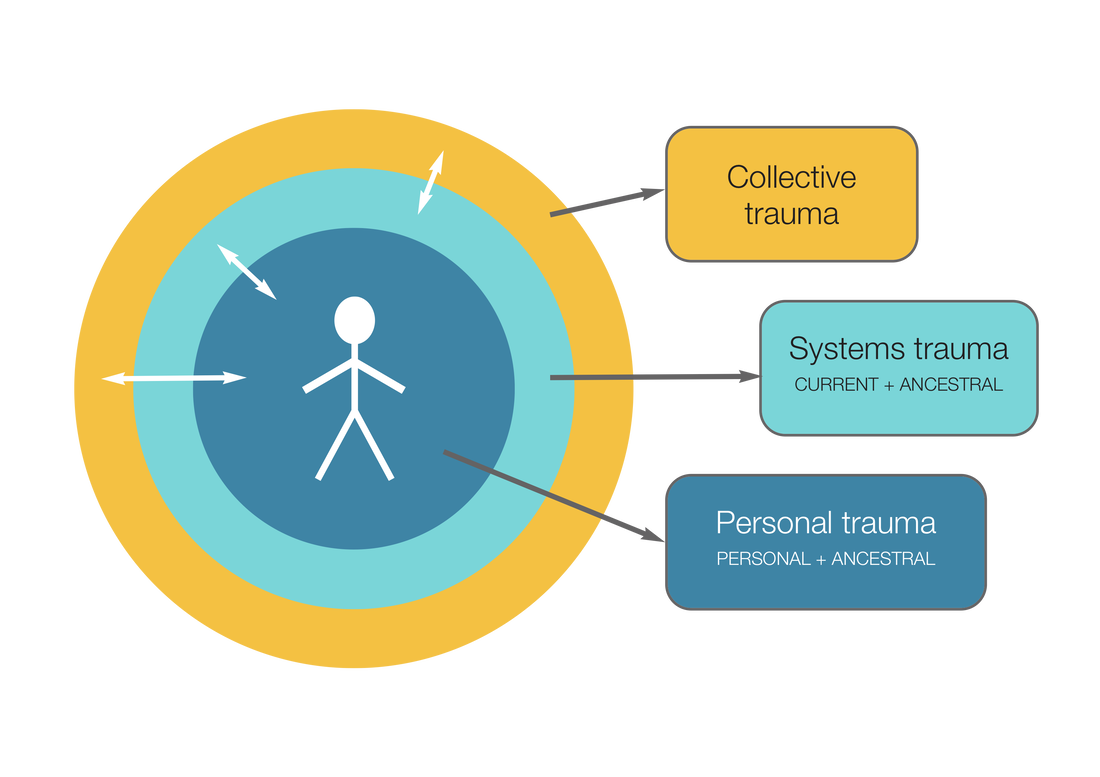

I thought I would set out what my current understanding is, though it is still emerging as I am still learnibng. I currently see Trauma Informed Leadership, as for all trauma informed work, as having three ‘layers’:

It is a big ask for any of us to hold all this in our conscious awareness and probably unrealistic to expect most leaders to. However, if we scale it down a bit, what it means for leaders is:

Ruppert6 has talked about how we live in a traumatising society and unconsciously continue to contribute to that continuing. Hübl’s book7 also looks at collective trauma and how it can be healed. On the programme I did with Hübl and others, many of the questions asked were from those in very traumatising situations wanting solutions. Understandably. However, the responses were to look within oneself first, to do our own work of consciousness raising about our burdened Parts and defensive strategies; we have to start there. I have also been on a few programmes with Roshi Joan Halifax8, in one she talked of moral suffering and identified four elements:

I shared these with an NHS group of coaches I was talking with some weeks ago and the concept of moral distress really resonated with them. They were seeing high levels of burnout, anxiety, and distress within staff and finding clients needed a lot more space to download and process emotions. These are symptoms of a traumatised system where the organisational components are resonating badly with the personal systems, causing these symptoms. Trauma informed leadership needs, I think, moral courage. Maybe we all do to live in a way that we are not contributing to the trauma around us. This from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing9: Moral Courage is the ability to stand up for and practice that which one considers ethical, moral behaviour when faced with a dilemma, even if it means going against countervailing pressure to do otherwise. Those with moral courage resolve ‘to do the right thing’ even if it puts them at personal risk of losing employment, isolation from peers and other negative consequences. Contained within this statement is the core of the issue – the risks that can result from standing up against traumatising policies and practices. Like many, I have coached whistle-blowers and heard how their lives and careers have been destroyed by those who didn’t want to hear the truth. Collective denial can be very punitive. A trauma informed leader would listen differently to such a narrative, would be sensitive to the risk that was being taken, enquire into it with a fully open mind willing to have to face difficult and challenging circumstances. What has this to do with coaching? If we are coaching leaders, it can be a field of reference we hold and if our clients wish to become more trauma informed and that is part of the contract then we can work with them to enhance the qualities needed to lead in that way. We may also need our own moral courage, to speak up to our clients if we experience them talking or acting in ways that deny the trauma in the system or will add to that there. This is where our supervision is always so helpful, to work though in ourselves what is happening for us, and from that position respond in a trauma informed way. While we are working our way through what all this means for us as individuals and coaches we all need to continue to do our own reflective practice and widen our perspectives about the wider field of trauma. 1.https://thomashuebl.com/ 2.https://pocketproject.org/ 3.https://meus.co.uk/blog/2022/03/08/dealing-with-organisational-trauma 4.Dr Richard Schwartz ‘No Bad Parts’. Sounds True; 2021 5.https://meus.co.uk/public/data/chalk/file/e/8/Meus%20Whitepaper%20-%20Organisational%20Trauma.pdf 6.Franz Ruppert. ‘Who am I in a traumatised and traumatising society’. Green Balloon Books;2018 7.Thomas Hübl. ‘Healing Collective Trauma’. Sounds True; 2020 8.https://www.joanhalifax.org/ 9.https://www.aacnnursing.org/5b-tool-kit/themes/moral-courage It’s encouraging to see more people talking about trauma informed coaching and developing certificated programmes. For a long time we seemed to be the only ones talking about it. I have developed my thinking about it over the last 4 years, informed by the many coaches I have talked with, listened to and been questioned by.

Here is my short version of where my thinking is at the moment.

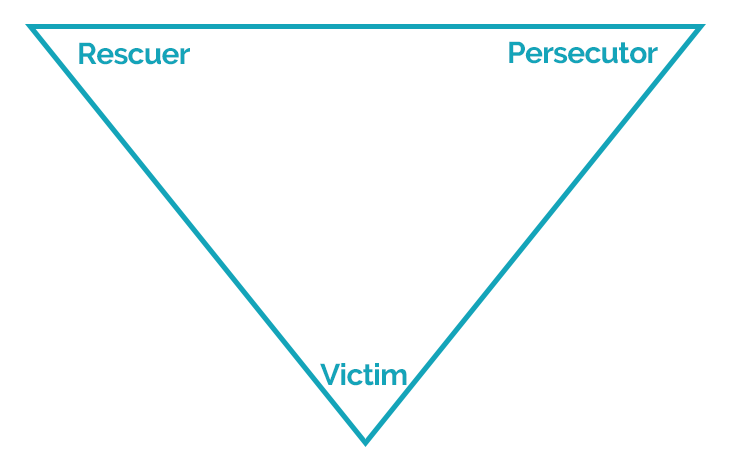

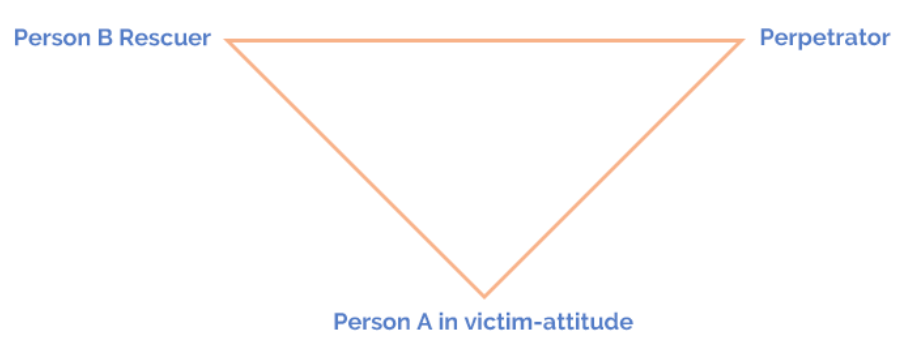

Being trauma informed covers this widening range of practice, as we can decide on basis of our interest and training where we want to place ourselves. We need to understand the lasting impact of developmental and shock trauma so that we can better be with and support our clients, including exploring whether working with a therapist may be helpful. The key factor for safe practice is that the depth of our understanding and extent of our skills has to match the needs of our clients. Where it doesn’t, we have the conversation with clients about what the best way forward for them might be. What are essential components of trauma informed coaching? I offer my thoughts as a stimulus for you to develop your own list or to add to mine. The maxim within coaching that ‘clients are resourceful’ holds no matter how traumatised they may present; our focus should stay with that so that we are not caught up in a deficit way of thinking and only focusing only on a trauma identity. We can help clients access and trust their healthy resources, bring unconscious patterns, or habits, of thinking and responding into conscious awareness where different choices can be explored. We can also offer clients tools to help their understanding and self-reflection. We can witness clients’ stories of pain and distress. If working more specifically with trauma, and are trained to do so, we can facilitate small steps in trauma integration. Trauma is the result of relationships and can only be healed in relationship, and we can offer a relationship within which clients can do their best reflection and gain self-awareness, they can ‘meet themselves’ in our presence if the conditions and contract allow. We all need to be experts in creating and holding a safe space for clients; we need to understand why safety is so important and develop a sensitivity to when a client (or we) do not feel safe. We can do this by working on our capacity to be present, grounded, self-regulated and resourced (by that I mean not tired or stressed out, and having access to good friends, supervision and colleagues to hold us in our work). We need to understand how safety is created and broken. We need to honour and work towards integration of our own trauma, with the help of an appropriate practitioner. This is essential in helping us become experts in creating a safe space as we are better able to manage our self-regulation, recognise when we are triggered by something and get the help we need to process that. To become more self-aware of our own patterns and habits, we need to develop compassionate inquiry; if we aren’t able to explore our responses to clients with compassion we will not step out of the old patterns. Trauma informed coaching is as much about the coach as it is the client, for me, even more so. None of us are diagnosticians and shouldn’t get seduced into thinking we are. We may form hypotheses, but we need to hold them lightly. Human experience is so varied we can’t make assumptions about how an experience in the past or present will affect an individual. We need a range of ways to facilitate the client’s self-regulation, supporting clients who are agitated, this includes breathing exercises, grounding exercise, mindfulness practice. Understand the concept and practice of co-regulation. If you are working in a more specialist way, you will need some additional interventions to support clients who are agitated and who find self-regulation difficult. As with all coaching, the agenda is the client’s. We have no permission to push them into places of enquiry they don’t wish to enter. Respecting their autonomy and right to set the boundaries they need to set is essential. Trauma creates a range of defensive behaviour and thoughts that often appear to an outsider to be self-damaging, but we can only let go of such patterns if we feel safe in our environment and have access to our healthy resources that can choose change. Clients can only go as far as they can go in the present moment. Our role is to respect that and encourage clients, if appropriate, to respect that in themselves too. We all need to treat our defences with respect and gratitude, as Richard Swartz says, ‘all parts are welcome’. If we are saying to clients we work in a trauma informed way, we need to be able to describe what that means in practice and have that conversation as part of the contracting. We can always recontract but making a shift in coaching approach during a session can be unsettling to clients. I talked at the beginning about respecting the boundaries of your competence where trauma and emotional distress is concerned. Crossing them often disrupts the safety experience of client. When in doubt talk to a supervisor. Develop skillful and compassionate ways to talk about what you are able to work on with a client and what you aren’t without giving the impression you are abandoning the client or scared of what they bring. It is a gentle dialogue to help the client think through what is best for them. Lastly but importantly, we all need good supervision to deepen our practice and offer the best to our clients. Let me know what you think, what I have left out and you think should be in; also where you disagree with me. Julia Vaughan Smith August 2022 APECS Accredited Master Executive Coach and Coach Supervisor M.A. Integrative and Humanistic Psychotherapy Photo by Steve Johnson I watched the recent film featuring the astounding Dr Gabor Maté. It’s called The Wisdom of Trauma (www.thewisdomoftrauma.com). It shows vividly how much dysfunctional human behaviour is explained by early childhood trauma. You don’t have to look very far, for instance, into any prison population to see how clearly this is true or to see what poor mental and physical health so many of these prisoners have. As a coach you may want to take one of the many Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaires to assess your own past. Here is one helpful article which also contains a questionnaire: Abuse, neglect, alcoholism – they’re all here. I took the questionnaire myself and my score was zero. This was not a surprise. I had loving parents who stayed together, I was an encouraged and cherished only child. I passed smoothly through the post WW2 education system, all of it free. Yet I have only recently understood that trauma has touched me too. My parents’ lives had been blighted by war, poverty, unemployment – and in my father’s case by a very unhappy relationship with his mother. Our small house was overcrowded and my parents had no privacy. This was because my mother’s father came to live with us and soon there was also the orphaned son of a close friend. Anger could not be expressed but it simmered away not far beneath the surface, enough to be perceptible and alarming to a child. Anxiety about security as it manifested through lack of money and questionable health was ever present and there is no way it could have bypassed me. After my father died I discovered a journal for the winter of 1947 when he wrote, ‘We don’t have enough food. Mary and I are holding back to make sure the children are not going hungry’. My role was to achieve through education what had been denied to my parents, something that they took for granted as desirable. I undoubtedly came to believe that love depended on academic achievement. I never remember being hugged or kissed and for certain I would have been left to bawl in my pram when unhappy or upset, as that was the dominant theory of childrearing at the time. These are extremely minor problems compared with having parents who abused, beat and neglected you, died, left – or who had chronic problems with depression, alcohol and drugs. Yet, as Gabor Maté, and other writers and thinkers such as Bessel van der Kolk, explain, the body remembers even when we don’t. Our neuro-physiology keeps the score. In my own case I have learnt that I must manage that drive to over-achievement. When I don’t, stress will trigger migraines, or more recently mysterious eruptions of hives and eczema. We need to beware as coaches of thinking that we are trauma-free, a wonderfully fortunate group of ‘Us’ who can gaze at ‘Them’, a traumatized population, with pity and wonder. Thank goodness that didn’t happen to us! But the chances are that something like it did happen to us, even if only glancingly. Maybe there are some wonderfully lucky people who have entirely escaped, but somehow I doubt it. As ever in coaching we start with ourselves. How far would our early experience be defining our own hot buttons? What form do these take? How might this have contributed to developing our own Survival Self? This is all part of why when coaching works it is because we are being a coach, the authentic person, not doing coaching. Photo: Gabor Gastonyi, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons AUTHOR: JENNY ROGERS The Compassionate Manager: A Trauma-Sensitive Approach to Managing in the Era of Covid-19 This article takes a helpful look at how bosses can help staff regain perspective and a better sense of emotional wellbeing as the pandemic eases: Our Covid-19 workplace (office and virtual) is going to become an even more integral part of how individuals and communities recover and heal. We will need employers to solve the immense logistical, physical, and psychological safety challenges that will allow us to settle into our version of the new normal. At the same time, we will be leaning heavily on managers to be completely committed to their evolving role... AUTHOR: JENNY ROGERS One of the resources within the mature integrated healthy self is the capacity to face the truth and take responsibility for ourselves and our behaviour. That is, not to look to others to take responsibility for us, or to deny the truth so we don’t take responsibility for our actions. Another capacity is to not take responsibility, or blame ourselves, for things we are not responsible for. The Drama Triangle, developed by Professor Stephen Karpman in 1968, illustrates the interpersonal dynamics that can arise between two people. It has given so many people such a lot of insight over the years. I think I have taught it to all development groups I have been working with. In trauma terms, all the adult roles here, that is victim, perpetrator and rescuer, are survival defences. The victim is in survival victim-attitude. This is not the same as the feelings of intense vulnerability, fear and rage from being perpetrated on which may be triggered by events in the here and now. We can acknowledge we are a victim of persecution, which is facing the truth, but not identify with victim-hood which is a survival defence against that knowledge. For example, if we slump our body, saying it is all useless or we are useless, or when we tell ourselves we are stuck, we give away our power and autonomy. In some ways this is to identify with the perpetrator who also took away our power and autonomy.

In Joan Halifax’s Standing at the Edge, she offers the idea of responsibility associated with these drama triangle rotes. She states:

I am currently writing about daughters, mothers and emotional trauma. The drama triangle is often a big feature of relationships held together by trauma. Daughters become ‘compulsive rescuers’; mothers are seen as ‘persecutors’ daughters feel they must appease or feel helpless to move away from; mothers can be in victim-attitude not taking responsibility for their life decisions; daughters may also become persecutors from their repressed hatred and rage. Halifax offers guidance to which I have added about stepping out of the drama triangle dynamic, and returning to resourcing and connecting with the Healthy Self:

The message for me as an adult is to take responsibility for my part in any difficulty. I can ask myself the question ‘in what way am I part of this?’. This is a useful for any event, whether an interpersonal one or not. It is also important when considering racism, misogyny, climate change and other systemic or societal themes. We can become a bystander or take up a victim-attitude towards it, thinking there is nothing we can do. It is essential we reflect on this from our healthy self, or there will be self-blame, self-recrimination, denial or illusion. Our contribution might not have been perpetration, it might have been a numbness, apathy, avoidance. blindness or normalisation. Otto Scharmer (https://www.ottoscharmer.com/) talks of three types of blind spots. Those I don’t see, what I see but can’t feel or connect with, what I see, sense or feel but can’t be bothered to act on. For example, I noted for myself this week something about my engagement with the sexual violence perpetrated on women. I see myself as a feminist and someone aware of all the issues. As part of that sense of ‘being involved’ I completed an online questionnaire Dr Jessica Taylor (@DrJessTaylor and author of ‘Why Women are Blamed for Everything’) was doing on this topic. I ended up shocked at the possibilities she suggested where sexual violence could be involved. I came face to face with my ignorance of the prevalence and realised I wasn’t really engaged. I just thought I was which isn’t the same at all. I completed it, thinking how fortunate I was to have been so untouched by such experience. Within a minute however, I realised that I had failed to acknowledge many of my experiences of sexual harassment, and that I had metaphorically ‘waved them away’. My question ‘in what way am I part of this’ was answered by my raising my awareness about my three levels of blindness. Photo by ryota nagasaka on Unsplash AUTHOR: JULIA VAUGHAN SMITH When talking about trauma with coaches over several years we have identified 5 common myths:

Let me unpick these. Successful people, like senior executives, are rarely traumatised‘Successful’ people are as likely to be traumatised as anyone else. Just because they have built a career or business doesn’t mean they may not carry trauma. In fact, the way they have survived and defended against the vulnerability brought by trauma, may have significantly contributed to their ‘success’. As long as their relationships with work, partners, others are giving them meaning, vitality and are not damaging their health they are unlikely to want to change anything about their life. If they carry trauma, it is not playing out negatively for them, at the moment. However, if they are affected by work-addiction, other addictions (including exercise, alcohol and recreational drugs), pending burnout, imposter syndrome, accusations of bullying others, feeling victimised, stress and anxiety or relational problems then these are signs of trauma survival strategies or survival self. Trauma only affects those who have had a horrific experience like a terrorist attack or serious car accident and who continue to have problemsTrauma more commonly results from our earliest experience from conception onwards. It arises from any severe stress the mother might be experiencing in pregnancy and from the relationship with our earliest and closest care giver(s). All forms of insecure attachment are examples of trauma survival. Those who have had a horrific experience are likely to be traumatised, as are those who return from armed conflict with a diagnosis of post traumatic stress disorder. However, this is a very small proportion of the population who are traumatised. Some recognise that sexual abuse as a child is traumatising, but I have also met those who deny the lasting impact, “I’ve dealt with it. It’s in the past’, whereas it leaves a lasting impact unless we do deep therapeutic work. The sexual and physical abuse of children is, unfortunately, much more widespread than we might want to believe. Some who grew up in a household where there was violence or anger similarly deny its lasting impact, as do those who went to boarding school at an early age. Trauma is an event that is remembered cognitivelyTrauma is the lasting impact on our neuro-physiology. It is a body-held response to a life threatening experience. It is not an event, but the impact of an event(s). The sense of our life being threatened is not a thought process but a response from those parts of our brain that stimulate the flight/fight/freeze responses that generate the trauma. The memory of the trauma experience is held in the implicit memory, that is without cognitive recall. It is a body-based memory, held there through our lives. It doesn’t go away over time. In fact, it might become more intense over time through being ignored or denied. We can have had traumatising experiences without having a explicit memory of it, there is no ‘video’ or ‘audio’ recall. People who are traumatised are visible through their mental health diagnoses such as PTSDPost-traumatic stress is a symptom of trauma. The majority of mental health diagnoses requiring treatment are also the result of trauma. However, more often trauma is not so visible; it is held very deeply in our awareness so as not to retraumatise us repeatedly. From there it gives rise to a range of survival strategies and personalities which are designed to keep the trauma hidden from view. The adaptive survival strategies and personalities, developed to keep us safe, become harmful or unhelpful as we get older. It is these that we meet in the coaching room, in the client and in ourselves. In this way the ‘there and then’ is living through the ‘here and now’. Trauma has nothing to do with coaching; and shouldn’t as it is dangerousTrauma does have something to do with coaching. Working with the trauma experiences is the province of therapy, not coaching; similarly working with Post Traumatic Stress. However, as we so regularly meet the survival strategies and personalities in coaching, coaches and supervisors need to have a trauma awareness to understand what they are meeting and why coaching these survival parts doesn’t work. Coaches need to recognise how their own survival strategies are getting in the way as well, we can’t coach from our survival parts. Unless we are trauma-aware, we will miss the information the client is giving us about their ‘there and then’ and be unable to facilitate them making links with the ‘here and now’. We will also fail to focus the work on their healthy, non-traumatised resources, which are able to challenge the survival narratives they have developed and the survival behaviour, which is what they say they want to change. If coaches work outside their field of competence, and coaching boundaries, they are failing to provide a safe environment for the client. This can be retraumatising for a client. However, this is also an argument for becoming trauma-informed, so you know where the boundaries are and don’t breach them unknowingly.

Find out more, and read the case examples, in my book ‘Coaching and Trauma: From surviving to thriving‘, available from online book sellers. Come to our Masterclass on ‘Trauma-informed Coaching’ in London on 25th June 2020,

The reality for many is that they are facing a lot of pressure from outside, reduced staffing levels and enhanced demands on their time and skills. Alongside this home life may also have many more pressures and stressors. At the same time, the ways we have used to relax and unwind, have fun, connect with others, are diminished in frequency or are just not available. There is no space for reflection.

As the pandemic and changing restrictions continue, these factors are having an unhealthy impact on emotional regulation for many. Coaches may not have had clients before in the same levels of emotional dysregulation as they are meeting in this phase of the pandemic. A new skill set is needed to be able to respond usefully to the presentation of these symptoms by clients. The first step is to have breathing and other techniques that support emotional regulation and a move towards calmness, that you can offer to clients. None of us can think clearly when we are in high levels of stress, agitation and/or anxiety; so deeper enquiry or analysis or thinking through actions that might be beneficial will not work until there is a greater calmness in the client’s system (and of course in ours). There are some great resources out there to support us. For example, I attended an excellent webinar by Dr Karen Triesman MBE a few months ago; it was a great reminder of ways in which we can support clients in this way. Her website generously offers a range of techniques and resources www.safehandsthinkingminds.co.uk . She works mainly with children and young people however, I recommend you look at the breathing and calming exercises she gives and how you might use or adapt them to your coaching. Be on the look-out for other useful exercises you might want to use. We first learn how to regulate our emotional responses and stress responses in childhood from those who are caring for us. They offer infants a sense of calm and reassurance in their faces, voice and touch. As infants we mirror them and our systems will calm down. Where this doesn’t happen, we are vulnerable to losing control of our emotions, and becoming hyper-agitated, as older children and adults. It is well known that people co-regulate; that is, when two or more people are together, they pick up the subtle signs of breathing and levels of calm or agitation, and mirror each other. In groups where there is a lot of agitation, people can reinforce that in each other. When one person is calm that can help the other person come closer to calm within themselves. if we can meet our clients in a state of calmness we are offering a mirroring experience for our clients. We can offer a breathing space for them, a chance to connect with themselves. If we are agitated ourselves that is not helping. Once there is greater self-regulation, deeper breathing, a sense of groundedness and more calmness, if the clients wish, we can then invite them to explore more what they might be able to bring into their lives or change for themselves – however small that might be – that would enable them stay calmer more of the time. This may require some habit changes and activities that they could bring into their lives to maintain greater calmness. Remember the importance of laughter too, are clients getting enough opportunities to have a good laugh? A good walk in nature? Attending to self-care? Celebrating small things? Once emotional regulation is established, clients may want to consider what survival defences from developmental trauma maybe contributary factors, for example, a drive for perfectionism, or duty, rescuing others, or feeling their needs don’t matter. They might recognise they are caught in entanglements or are on a pathway to burnout (see blog November 2020). The focus here is ‘what may be possible regarding changing their patterns of responding to the situation?’ We can also support clients think through how they may want to change the external circumstances. It might be that moving or leaving jobs feels difficult, but that can be explored as can other factors that may be possible in terms of changing the external conditions. Some employers may be demanding more than can be physically and emotionally given, and clients may face tough decisions. Some clients may feel they are not giving enough, so blame themselves, rather than the employer; this may have a connection with their early history. We can challenge that self-blame, if appropriate. If clients are so deeply affected, and beyond being helped by our coaching, they may need therapeutic or medical intervention to help reduce their anxiety. They may also need to take time off on sick leave. We can support them thinking how to take these actions. Continuing without release is physically and emotionally damaging to them. AUTHOR: JULIA VAUGHAN SMITH I have been rereading Joan Halifax’s book ‘Standing at the Edge’. In it she explores what she calls ‘edge states’ within six virtues (altruism, respect, empathy, integrity, engagement and compassion). She looks at the positive and negative expressions of them; the edge is the point where tipping into the negative is possible.

In her section on ‘engagement’ she talks of burnout, which she puts under the heading of ‘falling over the edge’. While having known about burnout for many years, I realised, with shame, that I had never looked into who identified and named it. From Halifax I learnt that it was Herbert Freudenberger, a mentee of Maslow (of hierarchy of needs fame). Freudenberger had been born into a Jewish family seven years before Hitler and the National Socialists came to power and, following his family having all their assets taken, was able to get to the USA on his own, aged 12. He was neglected by his step-aunt and had to find ways to survive on his own, including living on the streets. He was, apparently, a ‘driven man who worked 14 – 15 hour days until he died’. Halifax quotes his son “His early years, unfortunately, never left him. He was a complicated man and deeply conflicted because of his upbringing. He was a survivor” Those who are trauma-aware, will recognise signs of trauma. How wonderful though that this deeply conflicted and driven man brought understanding to the world about a condition that is widespread. I fear it is possible that Covid-19 may see more cases of burnout in those who are in people-facing occupations, dealing with low staff numbers and increased pressure, while wanting to bring compassion and care to those served. Freudenberger described burnout as being, I quote from Halifax, “…a state of mental and physical exhaustion caused by one’s professional life” and “…the extinction of motivation and incentive, especially where one’s devotion to a cause or relationship fails to produce the desired results .” Beneath the potential for getting burnout are our own issues concerning ourselves. These might arise from our own trauma and be linked with wanting to feel valued, wanting to rescue (what Halifax terms pathological altruism), an identification with our profession and an inability to create and maintain healthy boundaries. Where this is the case, there are always occupational areas willing to drive these people hard and expose them to enhanced stress. I read today that some NHS staff are working 36 hour shifts; they do so from their commitment to their patients and their profession and the system demands it of them. Halifax reminds us that it can be beneficial for some workplaces to burn us out as a way of subduing us; while rewarding us for ‘drinking the very poison of work stress’. Emotive words but I welcomed her stating the reality. Halifax, again talking of Freudenberger’s work with his colleague Gail North, describes the story line they described that leads to burnout:

With the inefficiency that inevitably travels with emerging burnout, we feel we are failing at what we set out to achieve and that is a step away from the work coming to seem meaningless. The issue, using survival language, is our entanglement with it. Maybe we need to be super-aware of the potential for burnout in some of our clients, especially those who are in the NHS, education and social care. I recognise that, as burnout is so common, many of you will be very familiar with its signs and maybe with its treatment. I remember a coaching demonstration at a UK Conference many years ago, where a very well respected coach was coaching someone with burnout. Many of those watching, said it was therapy and not coaching. The coach was robust in his view that he was coaching; I think the exchange was an example of how sometimes coaching pushes things away as being about ‘therapy’ rather than engaging with what the coaching contribution is to this client’s situation. Sometimes, of course, coaching may not the be best intervention, or we the coach might not be the best person, but that is something for us in supervision. Joan Halifax writes from the Buddhist perspective, a compassionate and inclusive approach. While there are a few elements that I take a different perspective on, I recommend her book for understanding these key virtues and navigating our way to ensure we don’t trip into the negative expression (her term) or into survival strategies (mine). The negative is harmful to us and to those we seek to help. Julia Vaughan Smith Halifax J (2018) Standing at the Edge : Finding Freedom where Fear and Courage Meet. Flatiron Books, NY The coach is puzzled. She has been working with this client for six months. His staff describe him as ‘cool’ and his bosses say that while they rate the high level of his technical skills, his inability to delegate is creating decision-bottlenecks for his team. They have hinted that he needs what they call ‘a more human touch’ as a better fit with the values of the company. The client works very long hours which he justifies by pointing out that this is an American owned firm and time differences make it essential for him to be available 12 hours a day, when, as he puts it, ‘California is waiting to pounce’.

In supervision the coach and I discuss what might be going on. How would she describe her own relationship with the client? No surprise here to learn that she feels she knows him no better now than in their first session. He is unfailingly polite but there have been several sessions cancelled at the last moment and others that have ended unexpectedly early. She feels he is keeping her at a distance. We review what she knows about his childhood. She says he was the oldest of four children in an army family. His mother suffered recurrent bouts of depression and his father was demanding and critical. As an adult his contact with his parents is limited to once a year short visits. Seeing our clients through the lens of ‘Attachment Theory’ can be so useful in situations like this. These ideas developed out of mid 20th century research conducted by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. It goes like this: we develop attachment styles as a response to the way we are parented. There are four styles: Secure, Anxious, Avoidant and Disorganized (you may encounter variations on these names). This client most likely has an Avoidant style. His needs for acceptance and love had been denied by a mother who was too preoccupied and unwell to attend to him and by a father who had been dismissive, cold and critical. He defends himself by holding himself in a safe place as the idea of closeness feels so frightening beecause of the level of hurt he experienced when he wanted contact with his parents. He learnt not to protest too much so has suppressed his own rage and needs, hence the sense of lack of connection. He didn’t learn about intimacy and closeness as a child. Behaviour with his coach mirrors his behaviour with everyone else in his life. Any suggestion of needing more intimacy triggers the need to withdraw, hence his pattern of cancelling or ending sessions early and of politely rebuffing his coach’s efforts to get closer. What to do? This coach has to recognise her own anxiety first and to fight her need to prove that she is adding value. It is tempting to start offering endless theories about leadership, suggestions of useful books to read, and the client might even welcome it as safely objective. But this is not the answer. Nor is it the answer with clients who display Avoidant behaviour to press them too hard for more disclosure. Instead, we have discussed how she might first suggest a detached look with the client at what his typical patterns of interaction are – and at their consequences. How much benefit might he see in changing them? If he does see some benefit, then it might be worth continuing. If he does not, then it might be better to settle for some extremely small and transactional gains. If he is prepared to change then she might suggest small steps with him to look at what happens when he does take the risks of being closer to people and whether he could benefit from widening the numbers of people where he took such risks. Maybe there is a part of him that would like to find different ways of responding to people. Which relationships does he feel already safe in? He might have some already. She might even suggest, very cautiously, that the coaching relationship itself was an example of one such relationship and a safer place than most to do some experimenting. The intriguing element in this is what attachment style the coach herself has, but that is another story. This is work in progress, so watch this space. We will be running a half day online workshop on Attachment Styles in Coaching on Thursday January 14 2021 at 1400. Jenny Rogers The Healthy Self is a dynamic entity, holding the capacity for self-regulation, autonomy, and our connection with ourselves. Its resources can be expanded through therapeutically facilitated integration of the cut-off trauma parts, and the consequent reduction of the survival self. However, throughout life we need to train ourselves to use the Healthy Self well, and to add to the resources it carries. This might involve abdominal breathing exercises, meditation, being out in nature, listening to music, having enough time to ‘be’ with ourselves and enjoy what that brings. This is about how we structure time and activity. The Healthy Self is about the present; the trauma parts are about the past, and the survival self is facing both the past and the future but isn’t in the present moment. Thoughts about how to develop healthy resources were stimulated by two events I participated in during August. One was a 5-day online retreat, the other was a one-day conference on ‘Facing Mortal Threat’. I recognise that we all take something different from the same event, but the things I took away included: Values or Virtues for living in the present and therefore from the healthy self:We need to know what is important to us, not our parents, not those we want to impress, but to our being able to live a life from a Healthy Self-perspective. I have always struggled when people talk about values, as so often what are listed don’t seem to me to be values. The word used in both these events was virtues, which I could connect with. What virtues do I want to develop in myself which build up the capacity within my Healthy Self? Some suggestions that I resonated with were:

Those of you who are familiar with Insight Mindfulness or Buddhism will recognise these. Healthy Self actionWe also need the capacity to act, it isn’t just about calming our system. But it is acting from the Healthy Self. On the ‘facing mortal threat’ conference, and one of the speakers used a term I hadn’t heard before, ‘toxic feminine’, which as a feminist I took exception to. I think he was referring to a potential danger in only focusing on calming (which I assume he was associating with the feminine) when we also need to act to use our autonomous agency. This might be in relation to our life or in relation to what is happening in our society. I took this on as an important resource within the Healthy Self.

Slowing down so the Healthy Self can breathe The acceleration of life was also discussed; everything is speeding up. I think we need to slow things down for the Healthy Self to breathe. Not into a sort of slumber, but to step out of the acceleration that is all around us and into which we are drawn. Covid-19 preventative measures have enabled this for some. Society is full of survival strategies to keep at bay the trauma feelings also present within us all. Survival Thinking Patterns During the retreat I also noticed how my thinking patterns were survival strategies. The planner, administrator, imaginator, and story teller were all busy when I was trying to sit and ‘be’. These thinking functions all have their value, but often they are about trying to control the future or reassure myself about the past; they are not about the now. And of course, part of my career was built on these thinking functions, leading large international projects or consultancy assignments. It is not that in themselves they are survival strategies, it is the use they get put to. They can crowd out the Healthy Self, shout it down almost. To develop my connection with my Healthy Self, enabling these to rest would be valuable. I encourage us all to explore whatever ‘virtues’ are relevant to us or whatever resourcing and deepening our Healthy Self fits best for us. What you decide on will be different from my selections. I think this helps us in our coaching, and whatever professional practice we are in. It helps diminish the extent and potential damage of our survival strategies. Julia Vaughan Smith Racial perpetration leaves the same trauma response as other forms of trauma and is as easily triggered, especially as there is racism embedded in our societies. I am noticing many more people are talking about racial trauma, and that it is coming into a wider collective awareness outside those communities for whom it is a common experience. Deliberate exclusion of any ‘group’ is perpetration and can feel life threatening especially for a child who may be bewildered about what is happening. TV images of perpetration and exclusion reinforce these personal experiences. Those affected have of course known and lived this. It’s the rest of us who may not have looked closely enough or listened well enough.

It reminds me a bit of when sexual abuse of children first came into the collective consciousness as being damaging; the children affected had always known and suffered the damage of course but this wasn’t recognised. Those understanding the impact for the first time were shocked and perhaps felt guilty for going along with the societal blindness. Sexual abuse sufferers were also afraid to speak out because of this denial held in society and its institutions, so they remained silent. The same can be true for those affected by racial perpetration, they have kept silent in wider forums; how could they trust how it would be received? The difference between sexual abuse and racial abuse is that with the former, while listening to personal stories I could often differentiate myself from the perpetrator, who was often male. We should remember though, that mothers and other women do sexually abuse children. With racial abuse, listening to the suffering in those that carry that trauma, I am more like the perpetrators, being a white woman, and indeed carry a societally complicit responsibility regarding the perpetration. As coaches we need to be able to hear clearly what is being said to us. We need to be able to make it a safe environment and to be open to all that may need to be shared by the client. This requires us to be aware of our own blindness, denial or discomfort and not to project them onto the client, whatever biography they share.. Thomas Huebl (https://thomashuebl.com) talks of three levels of trauma:

The recognition of transgenerational trauma means that we understand that ‘it didn’t start with us’ other than in very exceptional circumstances. Our grandparents’ trauma, and external conditions, affected how they parented our parents, and they in turn carried their trauma in their parenting of us. This trauma will have resulted from the wide range of possible causal factors, including, racial abuse. These causal factors include how our parents, or those parenting us, relate to us, from conception onwards, within the external conditions they are experiencing. The child might take in aspects of hypervigilance and survival responses they experience in their parents. There is some emerging epigenetic evidence in mice about how the DNA is changed by the trauma response in one generation. If the trauma response is somehow encoded into the DNA, as is being suggested but as yet unproven, then we inherit that. The genetic coding sets up a sensitivity to environmental conditions. If the conditions we experience replicate that, the trauma response will activate. The implication is that some have already been ‘primed’ to be sensitised to their environment. This is still ours to do the work on, to understand our trauma response and that while it is linked directly to our own experience, it is also linked to one or both of our parents. Collective Trauma is a relatively recent concept. We live in a traumatising and traumatised society. That is, that society holds the perpetrations, the fragmentation of trauma, and the survival defences against the trauma parts embedded within societal ‘norms’ and institutions. We take these in as part of our societal conditioning and exposure. We are all affected by these dynamics. Racism including anti-semitism is part of this collective trauma and affects all of us in different ways, depending on which race we are; for example, do we know these perpetrations directly or are we carrying denial, illusion and avoidance, or are we numb or frozen to it as part of our traumatised response? How are our institutions complicit in this collective traumatisation? How are we? Those who perpetrate on others also stimulate the trauma response within themselves. They too become more split, cut off, frozen, numb and utilise a range of survival strategies, the strongest of which are denial and justification, together with the perpetrator:victim dynamics. These are held in society structures and attitudes. There was a personal account on Twitter yesterday, by a barrister, who was repeatedly challenged by the court officials as she made her way to the court room she was to be in. She was talked to as if she was the defendant, the cleaner, and a relative of a defendant but all seemed to be blind to the fact she was a barrister because of her skin colour. This I am sure, is repeated in all kinds of settings, every day. The thinking is that doing our own work is an essential part of contributing to the healing of collective trauma. This means owning our own perpetration on others, taking responsibility for our part in the continuing collective trauma, or trauma within individuals. We are then more open to the reality of the world and the shared/unshared experience. A good reflective question to ask ourselves is “in what ways am I part of this?” in relation to specific events. We need to sit with the question and allow things to emerge, and meet them without self-attack, but to face up to our truth. Perhaps the best way to deal with all this is as a person, not just as a coach. To be a more effective coach we need to invest in our own inner development, alongside any other education and training. If we do our own work we are more aware of our contribution to the continuation to collective or systemic trauma. As coaches, we can be aware of this whole field of racial trauma in our work and continue to expand our awareness, through our education, reading and listening. We need to be mindful of parts of us that are numb or frozen to particular issues, or are in denial or become dissociated should an issue arise. Jules Vaughan Smith This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Coaching Today, which is published by the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (c) BACP. https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/coaching-today/ The military metaphors have become so common in the pandemic that we stop paying attention: it’s a ‘fight’, a ‘battle’. If so, then it’s one where the ‘war’ involves the ‘civilians’ as much as the ‘troops’. As coaches we are as much at risk as our clients and as likely to be affected by anxiety, hope, dread and sorrow as anyone we work with. This gives coaching in the time of Covid its unique challenges. In this article we explore why being trauma-aware is especially relevant at this point, what to look out for – in ourselves and in our clients.

Trauma awareness can add depth and richness to your coaching and it may be especially useful in this crisis. At the core of being trauma-informed is having clarity about what trauma is and how it manifests itself. We find the work of Professor Franz Ruppert (2014)(1) to be a helpful framework, as it is simple and yet captures the complexity of trauma. If you are unfamiliar with it, the box [below] is a summary. Professor Franz Ruppert Trauma ModelTrauma is a lasting neuro-physiological response to life threatening experience. This sense of life being threatened is a body-based response to conditions that are experienced as profoundly unsafe. This occurs in early infancy where there is insecure attachment from conception onwards. It can also occur later in life when we are in serious danger. Ruppert’s model (see figure 1) which he names ‘the split in the psyche’, offers a simple illustration of the complex response: The trauma response brings a ‘freeze and fragment’ reaction and shuts us down through dissociation. The feelings of terror, rage, shame and intense vulnerability are held within the trauma self and remain the ‘age’ at which they were experienced, so when expressed will be immature. To keep these feelings deeply repressed, we develop a survival self with a wide range of strategies. These continue to operate through life in the attempt to keep us from re-experiencing the trauma feelings. The healthy self is our innate capacity to be self-regulated. In that state we are able to face the truth clearly, make decisions for ourselves and do not need to manipulate or entangle others to get our needs met. We can tolerate our trauma feelings and are not frightened by them. It is the survival self and healthy self that we meet in coaching, in ourselves and our clients. The repressed trauma feelings are the focus of psychotherapeutic work, as is working with traumatic stress. Within individuals who are traumatised the ‘there and then’ trauma feelings are unconsciously stimulated as if the ‘here and now’ was the same situation. The core sense is of not being safe, of being at risk of hurt from others. The survival self contains different strategies including denial, control of ourselves, others and the world, use of addictive habits, depression and other signs of mental illness. It also develops a survival-attachment pattern, in response to insecure attachment as a child. When these survival parts are active and in the driving seat, we do not think clearly. We fail to assess the reality of our situation and the range of healthy resources we can draw on within ourselves to deal with that reality. See Vaughan Smith (2019) Implications for the pandemicMany of us use distraction to get away from inner pain – it is a survival strategy. The distractions we may have used previously may not be available in the same way. For all four of the clients we described at the top of this article, boundaries, necessary for feeling safe, have been disrupted. The journalist had not fully recovered physically or mentally and was shocked by having needed to be hospitalized, it had disturbed his idea of himself as fit and healthy. The social services manager was unable to protect her boundaries and the existing weaknesses in her marriage were ruthlessly exposed; she was overwhelmed by too many Zoom meetings, too many domestic responsibilities, feeling she need to be available all the time to everyone. The young teacher had developed her phobia and OCD as a response to an intensely traumatizing childhood where both her parents had been alcoholics, leaving her to manage the care of a younger brother. The pandemic recreated the intensity of the trauma she had experienced as a child: the world really was unsafe; there really were ‘germs’ everywhere. For the intensive care consultant, his difficulty in challenging senior managers reawakened the sense of impotence he had experienced as a small boy sent to boarding school far too young. What should coaches expect from clients at this time?Some coaches have raised concerns about what they should expect from clients as we move out of this situation and possibly into yet more uncertainty. Clients might be bringing unfamiliar issues, thoughts and feelings to the sessions. Our task is not to get caught up in the survival game of wanting to rescue them nor to shut them down to avoid our own anxieties. These are our own survival strategies as coaches. People whose survival strategies include work-addiction and perfectionism find rest difficult and often have poor sleep. They may also be addicted to exercise. Working from home with the family around can cause these tactics to over-heat. Clients may suffer from exhaustion and be nearer to burn-out than they were previously. The coaching focus here is: What will help you find rest? What parts of yourself can help you let go of these survival drivers? Whose help do you need? Some may need therapeutic help to get to the root causes of their survival drivers. Clients who use control as their survival strategy could be overwhelmed by the uncertainty. Their normal mechanisms for control may not be working: children interrupt, exercise can’t be done in the safe environment of the gym, who knows what their team members are up to when they are also working from home? The fear of being out of control can create high levels of anxiety. A senior civil servant client with major responsibilities described it like this: ‘All my routines are impossible. I used the long commute to create a welcome corridor between work and home. I had little rituals that helped: the coffee from Pret, the walk around St James’s Park at lunchtime, the pleasant chats with my PA. That’s all gone. Instead I have the dog, the cat, the guinea pigs, the kids, my husband, the shopping and the usual ceaseless political churn with Ministers to deal with as well!’ The frightened childFor some of us, this experience may awaken profoundly upsetting survival thoughts. The repeated use in the media of the word ‘isolation’ as in ‘self isolation’ may trigger feelings of having been isolated as a child, for instance having being hospitalised, passed through the fostering system or of being with parents who were unable to care for us. People who live alone may feel vulnerable where the lockdown experience reawakens early trauma. A good question here might be ‘How am I isolating myself now?’ If we feel uncared for in the present we may be identifying with times in the past when we were uncared for. The question here might be, ‘How am I failing to care for myself now?’ A client struggling to keep his business alive during the most intense lockdown phase found that he was once more using alcohol as his crutch, sleeping badly, reverting to an earlier style of working where he had found delegation difficult. The coach’s question here was, ‘How might you make looking after yourself the priority here?’ Letting go of guiltSome people, coaches and clients alike, have enjoyed the lockdown experience. They have no financial worries, they are relieved that they longer have to perform for others or seek their approval. They have relished the long walks in pleasant weather, they fall into the low risk category. Some have felt guilty about this enjoyment. The reality is that it isn’t either/or. We can feel privileged and compassionate for those who are not so lucky. The ‘shoulds’ are the clue to these being the equivalent of ‘parental injunctions’. The pandemic has exposed divisions and differences in the society we have helped create. Guilt is only useful if it triggers something we need to learn about how our action has transgressed our value system. Feel it, note it, move on. We need to be sure that whatever actions we take come from our healthy self and that it isn’t a reaction from the needs of our survival self for validation or rescuing. This was true for a previously hard-pressed Chief Executive who found that much of her charity’s work could be done remotely, and much of it without her. This prompted the question, ‘What would I rather have from now on, if I could have it?’ Some clients will have found new energies and capabilities through entrepreneurial or community focused participation. They might be energised and excited about how to take that into the next phase of their lives. One coach offered training and technical help on remote working to his local volunteer organisation. This was so successful and rewarding that he has decided to commit 30% of his working time to this organisation for the foreseeable future. Looking after yourselfAs coaches we need to attend to our own well-being. This means using knowing how to calm and regulate our breathing, to shut down negative thinking, to connect with our body and felt experience. Mindfulness, meditation, yoga, deep breathing exercises, walking, running, painting or image-making, keeping a reflective journal and being with nature – all of these may help. Don’t hesitate to consider coaching, extra supervision, counselling or therapy for yourself if you feel you may need more support as we move through and out of this crisis and possibly into new waves of it. If we can stay in our healthy selves most of the time, we can be with our clients in whatever the challenges they bring to us. We don’t need special ‘techniques’Coaches often ask us whether you need a unique trauma-aware set of tools and techniques. The answer is no. You don’t need any special pandemic-specific tools and techniques either. Your normal coaching skills, see Rogers (2016) (4) will be more than enough. Clients are not looking to us to reform or give them answers. Some approaches we have found useful include:

SummaryWhat we know is that all our clients will have a unique response to the situation. This will be a combination of their trauma history, survival and attachment patterns, and the actual reality in the here and now. Recovery will take time. For some it will be longer than for others. However, this experience is in our system and we will carry aspects of it with us for a while. Recovery is not to be rushed, renewal needs reflection, creativity and an investment in our physical health and wellbeing. The impact will resonate, and issues may continue to arise many months or even years later. We can’t all just pretend this didn’t happen. Connecting with others is a key component of recovery process. Clients may need support to rebuild healthy social or professional networks. We too, have to go through a recovery process and can help ourselves by connecting with peers and others to talk about what we are experiencing. We need to attend to ourselves so that we can be fully present for our partners, family and clients. Julia Vaughan Smith Footnotes

When we ran two catch-up seminars via Zoom for coaches interested in our trauma work, many of them people who had already attended one of our masterclasses, we asked for ideas about how to manage our own anxieties. Here is a selection of the many useful ideas that people put forward: Mindfulness and meditation: not surprisingly there were many fans for subjecting ourselves to the discipline of regular sessions, usually run online and free. One participant said, ‘I hate mindfulness and struggle to do it, but I found it was really helpful. I emptied my mind and it calmed me down.’ Jon Kabat Zinn got rave reviews https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4gZgnCy5ew as did The Compassionate Institute https://www.compassioninstitute.com/ https://www.umassmemorialhealthcare.org/umass-memorial-center-mindfulness Exercise and movement: people who were not necessarily fans of meditation have found that movement serves the same purpose. Ideas here included dancing along to music, walking in a beautiful place, running and jogging. Many people commented on how much it helped to make these pleasures a regular commitment. For those who like to follow a routine set by someone else, there are many free online tutors who cater for every level of fitness, for instance Lucy Wyndham Read https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCag7XoiJLutjBTsM0tAzUzg Deep breathing: the art here is to make the outbreath a lot longer than the in breath. Some people advocate breathing in through your nose and out through your mouth, blowing the breath out gently and imaging the stress leaving with it Progressive muscle relaxation: these well known exercises involve relaxing major muscle groups one at a time, for instance starting with your toes, working up to your thighs, torso, shoulders and face. There are many free videos and audio tapes available here, eg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1nZEdqcGVzo Adapting our professional practice: many coaches commented that although Zoom and other virtual platforms are useful, it is tiring to have long sessions. One hour sessions possibly more frequently seemed to suit many people. Then there is a whole range of useful tips on managing online work, for instance, turning off your own picture as it is disconcerting and distracting to see yourself constantly, something that in ordinary face to face work we never see. Volunteering: feelings of guilt, anxiety and depression may be kept at bay to some extent by volunteering. A lot of coaches are involved in a variety of schemes offering free coaching to NHS staff. Others are working at food banks or helping neighbours who are shielding. One of our participants described making scrubs and protective gowns for clinical staff. Pastimes which involve different parts of your brain! Jigsaws got a mention here along with knitting, gardening, listening to music, reading undemanding books and watching boxsets on video. Jenny Rogers Other resources:

Carole Pemberton (who attended one of our catch-ups) has written an excellent book very relevant to this topic. : https://www.amazon.co.uk/Resilience-Practical-Coaches-Carole-Pemberton/dp/0335263747 as has another attendee. Julia Steward. She has written about resilience for leaders in education https://www.amazon.co.uk/Sustaining-Resilience-Leadership-Stories-Education/dp/1911382845. NScience are a good source of ideas and inspiration on trauma and related topics. At the moment they are doing all their work online. This October evening webinar looks interesting – the Emotional Regulation Toolkit https://www.nscience.uk/product/the-emotional-regulation-toolkit/ Finally, don’t forget Julia’s much-praised book, Coaching and Trauma which you can get from Amazon or from Jenny’s website: www.jennyrogerscoaching.com Our next masterclass will be done online in two parts Dates: Sept 22 and Sept 29 2020 I am sorry to start this blog by being pedantic. Covid-19 isn’t a trauma, circumstances never are. The trauma, as many of you will know, is the lasting impact on our neuro-physiology of the flight, fight, freeze and collapse response of the nervous system to our life being in danger. It is a body based response. Of course, for some, the virus and the policy responses to it, may reawaken old trauma pathways, and present as intensified anxiety and survival strategies. Re-emergence or intensification of previously diagnosed mental health conditions may present; and some people may need to seek help for the first time for intensive anxiety states and depression. These symptoms are not so readily helped by coaching other than in facilitating thinking about what action is needed to re-establish emotional well-being. That action may be medical or therapeutic.